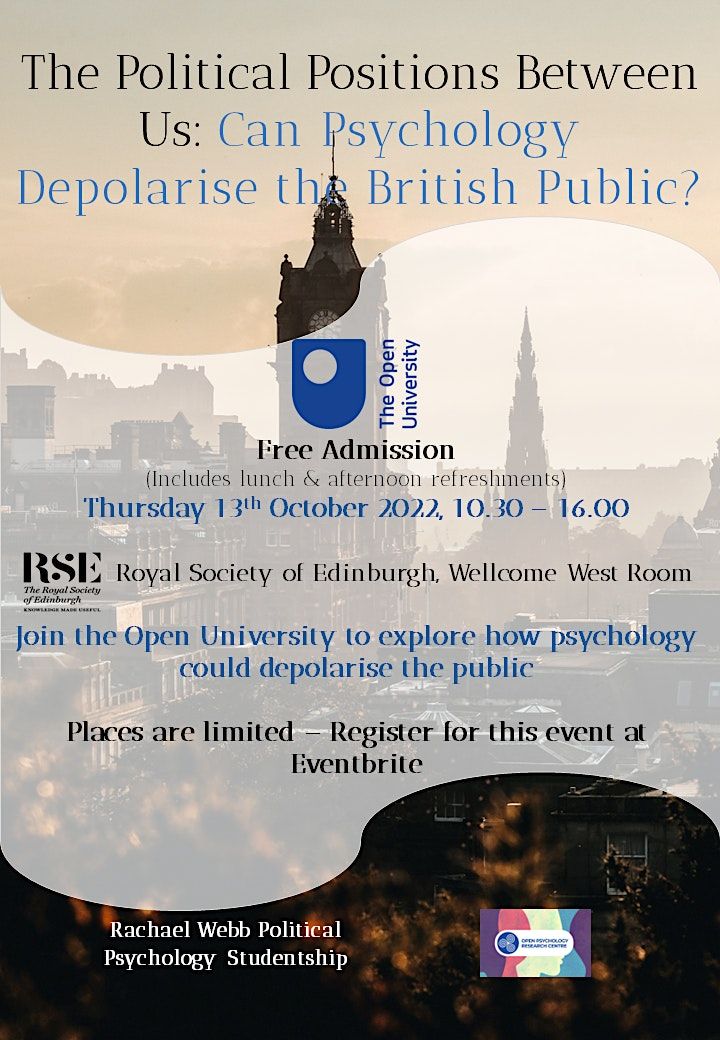

The Political Positions Between Us: Can Psychology Depolarise the Public?

Schedule

Thu Oct 13 2022 at 10:30 am to 04:00 pm

Location

The Royal Society of Edinburgh | Edinburgh, SC

About this Event

The Open University warmly invites you to the Royal Society of Edinburgh's Wellcome West Room to explore how social psychology could depolarise the British public. Kindly funded by both the Rachael Webb Political Psychology Studentship and the Open Psychology Research Centre, this intimate event is open to the public, policy-makers, and researchers alike. This knowledge transfer event offers a thought-provoking opportunity to interact and discuss political polarisation with the following experts and innovative new researchers:

10.35 Welcome, Polarisation and the Public Dialogue Psychology Collaboratory.

10.45 Dr Ana-Maria Bluic (Dundee University)- Harnessing the positive, transformative power of dissent on social media

11.30 Dr Tabitha Baker (Bournemouth University) - Understanding the political psychology of defence mechanisms

12.15 Lunch (East Wellcome Room)

12.45 Dr. Kesi Mahendran (Open University) - Playing politics: The art and science of handling political power.

13.30 Kate Holliday (Edinburgh University) - How framing a controversial issue influences political actors and debate.

14.15 Afternoon refreshments (East Wellcome Room)

14.30 Dr Anthony English (Open University & Lancaster University) - Exploring how politically polarised individuals can sustain dialogue on a vexed issue

15.15 Dr Sandra Obradović (Open University) - How to challenge stereotypes and remove group boundaries during political discourse

Presentation Abstracts

Dr Ana-Maria Bluic

For many years, research on political polarisation was dominated by US studies with a focus on partisan polarisation (i.e., the ever-increasing animosity between Republican and Democrat politicians and their party supporters). As research in the field has expanded beyond the US context, a more nuanced understanding of polarisation was developed. As such, researchers started making distinctions between affective polarisation (when distancing between groups is driven by “outgroup hate rather than ingroup love”) and issue-based or ideological polarisation (when distancing between groups is driven by disagreement on policy issues which can go across party lines, such as in the case of Brexit). Here, I discuss the benefits of understanding polarisation as both an affective and an ideological process. My main argument is that having an evidence-based, cohesive, and nuanced understanding of this process is essential for how successful we are in addressing the issue of polarisation. While the existence of competing beliefs in a society is sign of a healthy democracy, unchecked polarisation driven by such beliefs undermines societies, most directly by opening a pathway to radicalisation (which in turn can result in political violence). Research using modelling approaches - that can account for the boosting effects of social media on polarisation - suggests that once that we have diverging beliefs in a society, without any intervention, the interaction between people from opposing camps will always lead to the formation of polarised groups. Therefore, the key question is perhaps, not how to fully stop or even reverse polarisation, but rather how to find ways to slow down the process to a level where we have civil disagreement, but not affective polarisation. In other words, how do we reach and maintain a state where we have moderate levels of ideological polarisation, so that healthy debate between opposing camps is still happening, but there is no real hate and psychological distancing between these camps? The approach to polarisation I discuss here also highlights the importance of collectively shared beliefs and the dynamics shaping them, including the role of media and communication on social media platforms. In conclusion, I propose several ways in which communication on social media can help us harness the positive, transformative power of dissent at the same time asserting control on factors that can drive affective polarisation between opposing ideological camps.

Dr Tabitha Baker

The United Kingdom has undergone significant political changes in recent decades; UK devolution, increasing globalisation, the political fall-out from the 2008 financial crash, Brexit, and the global COVID-19 pandemic. The circumstances of these events have led to rapid social, political, and economic polarisation, contributing to a sense of wide-spread division, uncertainty, and anxiety amongst the voting population. Numerous narratives have dominated academic and political debate on such themes, and a powerful dynamic that underlies these is the strength, influence, and power of psychological qualities such as emotion, identity and belonging. The research presented in this presentation will pay close attention to how these psychologically driven political patterns and sentiments play out on the ground, using evidence from in-depth interviews with voters in England in 2020. The psychological approach will primarily draw upon psychosocial studies, a field that seeks to investigate the ways in which the self, psyche and society are interconnected. This approach focusses on these interconnections between the ‘inner’, our individual psychology, and the ‘outer’, the society we are positioned in. Psychosocial approaches enable understandings of identity, behaviour, conflict, and attitudes that we experience in political life. This presentation will illustrate how such psychosocial processes might influence political thought and account for the ways in which people think and act in polarised political climates. This, in turn, will demonstrate why it’s important to look beneath the surface and understand politics’ emotional impetus. Particularly, how the affective roots and drivers of loss, fear and anxiety can trigger defence mechanisms to manage them, and what this can look like in politicised settings.

Dr Kesi Mahendran

Accusing another person of playing politics – suggests that they are hijacking the issue or being inappropriate to the situation. This position implicitly suggests there is a common-sense view that the good citizen is not political. Or at the very least knows that there is a time and place to avoid talking religion or politics. Yet across the world the mechanisms of direct democracy are increasing from the use of direct referendum voting to the rise of social media platforms. Rather than meeting houses, agora and public squares the rise of direct democracy means we are mobilised and manipulated at every turn. It means that from our mobile phones we can potentially gain worldwide attention. This talk examines democratic skills and the art of handling political power in the digital age. It first explores the distinction between being political and being civil. Then, drawing from the 2019 Citizen Worldview Mapping Study conducted in Edinburgh, Manchester and Stockholm, the talk will reveal what happens when the public are given the political power to rule the world. It shows how the public hold onto political power, create political power and finally the circumstances when they might choose to give it away.

Kate Holliday

My research looks broadly at framing within ‘policy controversies’, seeking to examine how the ways in which an issue is framed by political actors and debate participants will have the effect of shaping the discussion, influencing how the issue is perceived and which policy solutions are appropriate to tackle it. Frame analysis is a tool which, when applied to political and policy studies, looks for underlying meanings in how an issue is being represented, for example, who or what is to blame for this problem, how this problem should be tackled, and even why it ought to be considered a problem in the first place. In political debate, we can observe competing and conflicting frames, as different stakeholders hold and put forward distinct ideas about what the issue is, and what is relevant to consider when tackling it. Situating frame analysis within contentious and intractable policy disputes allows for the consideration of how frames can both be influenced by, and work to exacerbate, political polarisation and tension. Investigating frames – as well as considering the political and institutional contexts they operate within – can produce a detailed and close analysis of how different political actors are representing a policy problem, and can expose the conflicting understandings and assumptions within these contrasting representations that impede productive and thorough debate. The case study for this research is the ongoing debate over proposed reforms to the UK Gender Recognition Act, as an example of a ‘policy controversy’ with highly polarised opinion and far-reaching impact. The primary methodology will be a frame analysis of relevant policy documents, examining how the issue has been represented by governments and other stakeholders, and how this framing has evolved over time. Interviews with key actors will be used as a secondary methodology to gain wider insights and reflections into the policy process and debate. These methods will allow the research not only to explore what ideas and beliefs are underpinning the prevalent frames in this debate, but also to consider the wider impact and role of political institutions, and to reflect on how framing can work within these contexts to shape and constrain debate and policy outcomes.

Dr Anthony English

The four years, twenty-seven weeks, and two days between the UK’s 2016 EU referendum vote and final trade deal have been some of the UK’s most polarising times. A troubling outcome has been the heightened antagonism between citizens on the UK’s future global relationships. Such polarisation has presented psychologists with a challenge; namely, to understand how polarised political actors can engage with one another to sustain dialogue on this issue. This two-study research focuses on the political positions individuals adopt and how this could offer a means of connection when discussing the UK’s post-Brexit world relations. Study one explored the positions adopted to Brexit-based and world map stimulus among a sample of 28 residents in England (Seaburn) and Scotland (Dundee). The second study paired 10 of those interviewees together on both shared and divergent political positions. An online discursive context was created to allow interviewees to re-adopt shared positions from study one before a researcher-led rupture exposed the pair to relevant polarising material. The focus being to explore if sharing core political positions allowed the interviewees to sustain dialogue. The presentation concludes by offering preliminary steps towards a different understanding of how individuals could sustain dialogue during politically polarising discourse.

Dr Dr Sandra Obradović

How do we enable people to talk about political differences without reducing each other to stereotypes or questioning each other’s rationality? One way is to begin to identify when and how people do this in dialogue. Drawing on focus group data collected after Brexit, my talk will illustrate how people, through communication, reduce and reject different political opinions, and in doing so, dismiss different political opinions as invalid and irrational. I consider moments where these processes are disrupted in dialogue, and how we can draw on those disruptions to challenge stereotypes and remove group boundaries.

Where is it happening?

The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, United KingdomEvent Location & Nearby Stays:

GBP 0.00